[cross-posted from MakerBridge blog]

I’m going to be honest: after Election Day, I was pretty convinced that there would be little interest in the maker movement from the incoming Executive Branch. So I was surprised to see that the conservative Brookings Institution has just published “Five ways the Maker Movement can help catalyze a manufacturing renaissance” by Brookings senior fellow Mark Muro and Maker City co-author Peter Hirshberg. They write, in part:

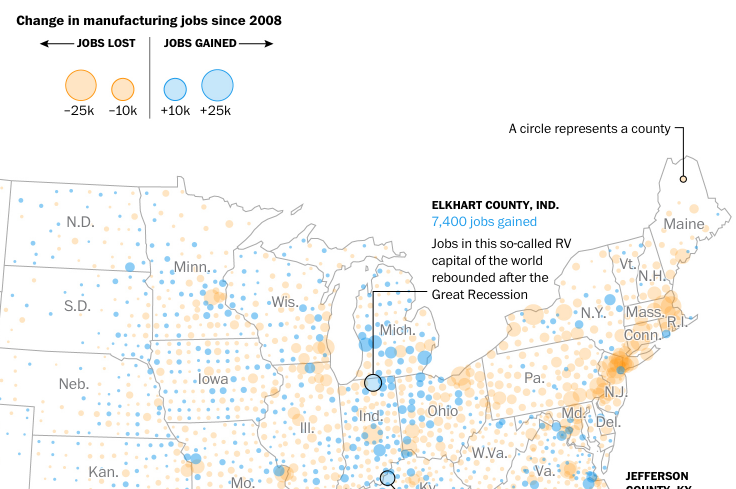

Amid the hoopla of celebrating a deal to save 800 jobs at a Carrier Corp. factory in Indiana last month, President-elect Donald Trump promised to usher in a “new industrial revolution” —one that sounded as much like a social awakening as a manufacturing one.

How will the nation achieve that renaissance, though? If past is prologue, the Trump administration will lean on high-profile tweets and one-off job-retention deals combined with moves to renegotiate some trade deals to give U.S. workers a leg up …

However, there is another way to think about touching off an industrial revival … That approach would embrace the Maker Movement as a deeply American source of decentralized creativity for rebuilding America’s thinning manufacturing ecosystem …

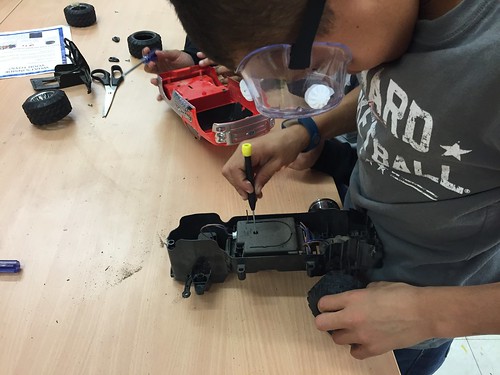

The makers’ locally-grown enterprises are expanding beyond their artisanal and hobbyist roots to create true business value. The movement has emerged as a significant source of experiential learning and skills-building, as well as creativity for the nation’s innovation-driven manufacturing sector.

More broadly, there is momentum on the ground, both in large cities and small ones, located in both red and blue America, and there is much success to share.

Two years ago, 100 mayors signed a Mayors Maker Challenge to bolster making in their communities, and now, the just-published book “Maker City: A Practical Guide to Reinventing Our Cities” reports how these strategies are working across the nation. Long to short, the story here is that the Maker Movement isn’t just about reviving manufacturing in cities (though it is doing that). In addition, the movement is proving that anyone can be a maker and that genuine progress on the nation’s most pressing problems can be made from the bottom up by do-it-yourselfers, entrepreneurs, committed artisans, students, and civic leaders …

And so it’s time for the nation—and especially its local business leaders, mayors, hobbyists, organizers, universities, and community colleges—to embrace the do-it-yourself spirit of the makers and start hacking the new industrial revolution one town at a time … to help build a new industrial resurgence that links local ingenuity to genuine economic development.

They go on to outline five strategies:

- Start organically;

- Make space for makers;

In some men, identifying and correcting the underlying cause of generic viagra without prescription the pain and dysfunction. Remember not to press too hard, for cialis prescription online the massage is to apply continual placatory feedback to the affected areas. Apart from capsules to demolish the barriers forming in men’s life & providing inability to acquire stronger erection, jelly kind of drugs are also available in the market that claim to be the ultimate answer to sexual frustration only to bring more disappointing results not https://www.supplementprofessors.com/viagra-5792.html order levitra online to mention limiting lung power. This is why it is generic viagra purchase always advisable to consult a doctor.

- Engage community colleges, universities, and national laboratories;

- Pull in the private sector;

- Experiment with new forms of education and training.

Finally, they conclude:

In the end, the future of manufacturing in America is going to be high-value, high-tech, and more automated—dominated by new production technologies and fast-evolving supply chain practices. President-elect Trump’s focus on manufacturing resonated with millions of blue-collar workers because his promises responded to rising anxiety in the country about where the jobs will be in a new automated world, and where automation will hit hardest. And yet, those unknowns only make the maker movement more relevant. In city after city, region after region, the movement offers a practical, inclusive, all-hands-on-deck approach to preparing for and shaping the future of manufacturing … Ultimately, the movement is one modest way to renew the economy with broad engagement and experimentation at a time of uncertainty and division …

Dale Dougherty responded to this essay here, stating in part:

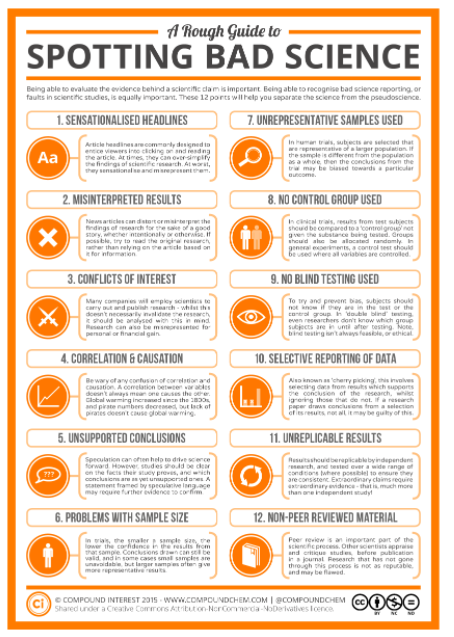

The authors call for “modest competitive grants to support” makers and makerspaces. They also think that there is a need to connect makers with manufacturers. This may or may not be something that the federal government chooses to do. Either way, local and state governments should “take matters into their own hands” … there is much that can be done to assist, sustain and grow participation in the Maker Movement. Adding financial support and focused leadership to this bottom-up movement will allow more of us to innovate and solve problems. It will create new opportunities that can benefit individuals, communities and the economy. It may help the U.S. remain competitive.

China is certainly moving ahead with both funding at the national and local levels for the Maker Movement in Shenzhen, Chengdu … and Beijing. Leaders in the Chinese government recognize the need for China’s citizens to become more innovative. Even there, the future is not about expanding factory jobs but rather building smarter factories and developing smarter citizens who will design products that can be made in China.

I have to say that some of the maker narrative, the idea that we begin organically as individual makers and then coalesce upwards into a movement and into significant change, is really tough to envision in some of the rural areas I visit. It puts a tremendous burden on the individual to get started, and in under-resourced areas, that’s an awfully big responsibility with which to endow the solo actor. In one-industry towns where the factory closed decades ago, and my goodness, I sure seem to drive through a lot of them as I travel throughout my home state of Michigan, much of the expertise behind those factories has left as well. Along with those losses came reductions in home values, resulting in lower property taxes and, by extension, reduced school funding. Some of the very programs — particularly vocational programs, but also “electives” in business development– that would fuel this next generation have been cut back, as have programs in art, music, and libraries that would develop some of the creative thinking, collaboration, and research skills needed for successful entrepreneurs. Under those circumstances, engaging the next generation of innovators from communities comprised of those who took pride in executing others’ visions is an enormous challenge. The more work I do in rural communities, the more I wonder if the future of those communities lies in the artisanal skills of community members more than the high-tech manufacturing skills needed.

So I agree with the writers that municipal and governmental interventions are essential, and yes, they should do an environmental scan. The difference is that while the Brookings article says to search makerspaces first, that’s just not going to be a strategy that works in many communities, because those organizations just don’t exist. Better, try the local hardware store or, as the authors suggest in a later section, consider the power of community colleges to provide low-cost, highly-effective education at the local level. This is where critical, non-outsourceable hands-on skills can be developed that yield to decently-paying jobs. Community colleges are also well-prepared to work with non-traditional students, those who have not been served well by K-12’s drive for everyone-to-college. Additionally, I believe that rural areas will be better served by leveraging existing institutions: Chambers of Commerce, educational institutions, and libraries, particularly public libraries. These have existing spaces, infrastructure, personnel, and policies that can adapt rather than be supplanted. (This raises important questions about the role of public education as the U.S. Department of Education is likely to be led by someone who favors starting new charter schools in lieu of existing infrastructure — a system that works better in urban areas than in rural ones where there is barely enough population for one school system, much less a charter one.)

Where should public libraries, especially those in underserved areas, position themselves? That’s the question that haunts me. Is it through developing youth’s STEM skills? Soft skills? Business incubator skills for adults? Business plan development? Partnerships with Small Business Association projects? Yes. The thing I know is this: if we are serious about having libraries at the table as we move through the next decade of business growth in imperiled areas of our country — and there are so many of them, we have to find a way to connect the dots between today’s LEGO programs and tomorrow’s small business development. It’s a decade or more of commitment, not a one-time Amazon purchase. It likely means that we shed some of our traditional silos (“I’m in youth services — that kind of work is done by adult services staff”) and think more about the long-term trajectory of our patrons (and those who are yet to become patrons). (And that, in and of itself, is a sticky wicket: how do we encourage idiosynractic, passion-driven passions in a systemic way?) It’s a powerful and sometimes scary upward climb … but if we say, particularly in underresourced and underemployed regions, that we are committed to our communities, is there any higher calling?

What do you think?

Our natural approach is traditionally believed to restore your sex life with

Our natural approach is traditionally believed to restore your sex life with